Social and Behavior Change Indicator Bank for Family Planning and Service Delivery

Également disponible en français

This family planning (FP) indicator bank is a collection of sample indicators specifically for use in social and behavior change (SBC) programs. SBC indicators for FP are often not standardized, making it difficult for smaller implementing partners to identify indicators as well as limiting cross-project and cross-country comparison of data. The purpose of this bank is to provide illustrative quality indicators specifically for global programs using SBC approaches to address FP challenges.

This indicator bank was developed by Breakthrough ACTION using a consultative process with key implementing partners. The resource builds on well-known indicator sources such as MEASURE Evaluation’s Family Planning and Reproductive Health (FP/RH) Indicators Database as well as from Performance Monitoring and Accountability (PMA) 2020’s recommended FP indicators. This indicator bank includes modified versions of indicators from these banks as well as additional novel indicators. Indicators should be adapted to local programmatic and cultural contexts, as necessary.

This indicator bank includes a subset of SBC indicators for service delivery. The purpose of this subset of indicators is to standardize the ways that implementers measure their SBC for service delivery activities. The majority of the service delivery indicators are for FP programs. However, the bank also includes some general SBC indicators that could be used for other types of programs. The service delivery indicators aggregate existing, validated monitoring and evaluation indicators.

How to Use this Bank

While the bank provides useful indicators for monitoring and evaluating SBC FP activities, it is not an exhaustive list. In addition, the bank includes more indicators than programs will find feasible or helpful to measure. As a result, users of the bank should select the indicators that align best with their program. Users can sort indicators by different criteria, including service delivery, and download indicators of interest. Indicators can be sorted by type; they are also searchable by key terms such as “gender” and “provider-client communication.”

Potential data sources are provided for each indicator. A data collection method should be selected based on the level of funding available to the SBC program, the capacity of data collection staff, time and what inferences or questions need to be made. For example, while client exit interviews may be a great way to monitor an SBC intervention and see if health provider counseling activities are working, it will not allow a program to generalize about the entire population living in a health clinic’s catchment area. When using these indicators, consider what data collection method best suits a program’s needs and realistically aligns with available resources and constraints.

Users of the bank should also consider that when measuring indicators focused on modern FP methods using quantitative surveys, the relevant indicator represents a composite comprised of a battery of questions specific to each individual method. Although this approach requires a greater number of questions and may increase the burden to participants, it is important to avoid a single question with jargon such as “modern contraception” that survey participants may not know. If asking a battery of questions is too burdensome, then a more generic question about FP methods, in general, may be more appropriate, losing its specificity to modern methods but more reliable and valid in the resulting data.

Indicator Types

The database also organizes the indicators based on four levels of monitoring and evaluation along the monitoring continuum (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The monitoring continuum

Outputs are defined as the activities, products or services developed by the program. Outputs reflect the efforts made by the program to influence the intended audience. An example of an SBC program with community-based activities might include the number of facilitators trained to lead community-level sessions for youth in the community.

Reach and coverage are the percentage and number, respectively, of the intended population that has received, participated in, benefited from or have been exposed to the program activities. Coverage primarily refers to the number of people “covered” by the program activities. Reach refers to the percentage of the population exposed to the program and requires structured interviews like surveys.

Intermediate outcomes are “behavioral predictors” or antecedents of behavior. At the individual level, intermediate outcomes may include factors such as knowledge, attitudes, intention, self-efficacy, and so forth. At the community level, they may include leadership and participation. Indicators measuring intermediate outcomes require some type of structured interview.

Behavioral outcomes are the specific actions ideally taken by an intended audience. These outcomes refer to actual changes in behavior that are measurable (e.g., the use of FP methods). Positive behavioral outcomes such as spacing births may ultimately lead to improved maternal and child health outcomes. Behavioral outcomes are generally measured through structured interviews or surveys, but there are indirect methods, such as clinic attendance records or product sales, that can serve as proxies for behavior. The service delivery indicators are broken down by provider behavioral outcomes and client behavioral outcomes.

Levels of Indicator Measurement

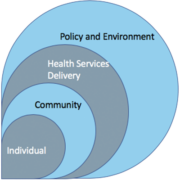

This indicator bank groups indicators by four levels of the social-ecological framework — individual, community, health services delivery, and policy and environment (see Figure 2). This is in recognition that there may be multiple influences on whether an individual performs a specific health behavior, such as interactions they may have with their partner or service provider, norms in their community, and national policies (Sallis, Owen, & Fisher, 2008; Storey and Figueroa, 2012). Addressing such influences across multiple levels can make SBC interventions more effective. Program indicators may be measured at multiple levels as well, although many are typically measured at the individual level to approximate constructs at interpersonal or community levels.

Figure 2: Potential levels of influence on FP behaviors

- Policy and environment – Indicators at this level monitor political will, policy changes, national coalition-building, and resource allocation that create opportunities for communities and individuals to live healthy lives.

- Health service delivery– Indicators at this level monitor the behavior of health service delivery teams in terms of their use of SBC materials.

- Community – Indicators that monitor community mobilization efforts typically fall at the community level. These include indicators about participation in community events and the role of community leaders.

- Individual – Indicators that monitor change at the individual level include those that measure recall of messages, knowledge, self-efficacy, intention, behavior, perceived social norms, and attitudes for clients and providers. They also include proxy indicators for the health service delivery and community levels such as perceptions of health provider communication and competence or perceptions of community social norms.

SBC for Service Delivery

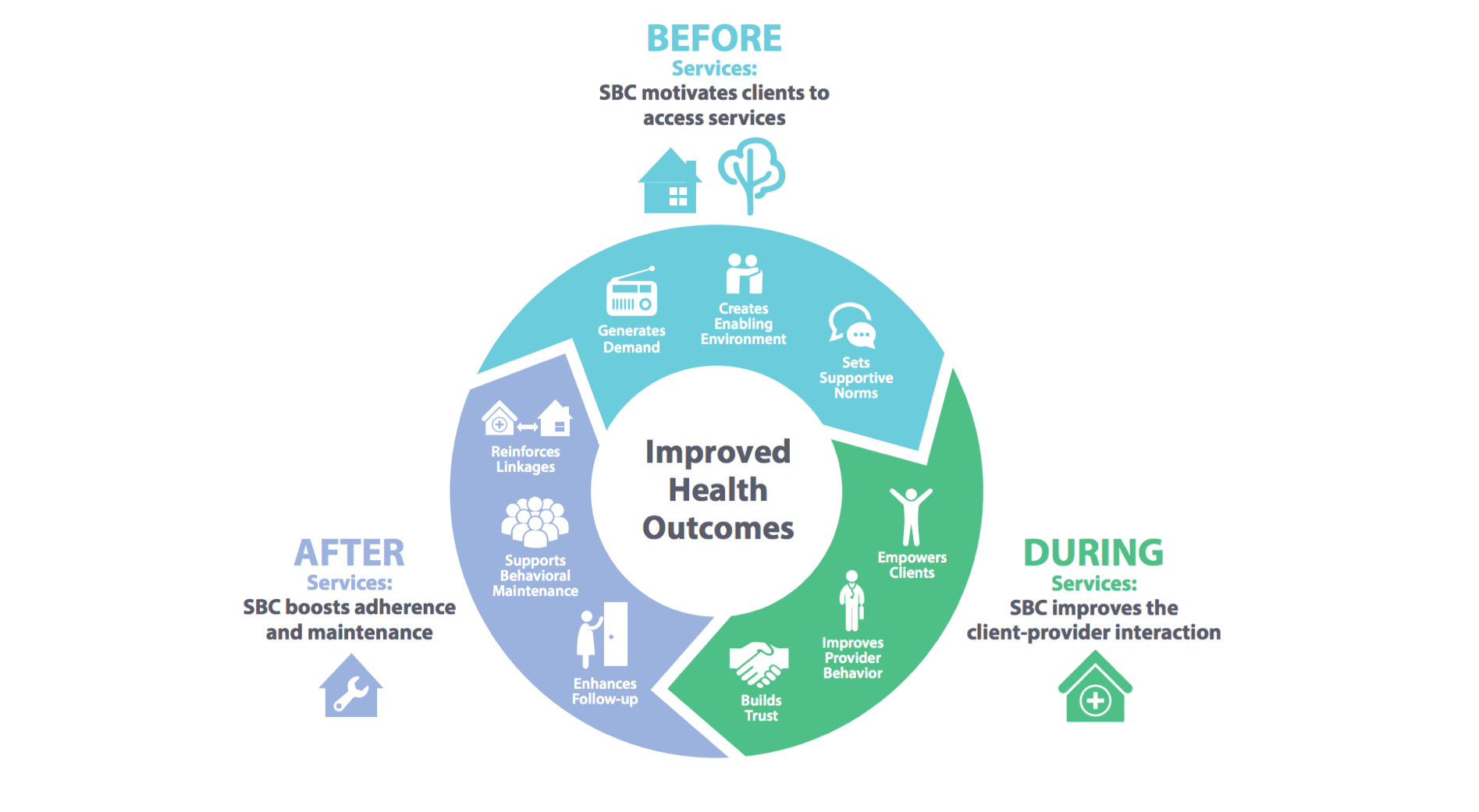

SBC for service delivery refers to using SBC processes and techniques to motivate and increase uptake and/or maintenance of health service-related behaviors among intended audiences. The Circle of Care is a holistic model that shows how SBC can be applied across the service continuum—before, during, and after services—to improve health outcomes. SBC for service delivery is distinguished by its focus on service interactions: the use of SBC to motivate clients to access services (before services); to improve the client-provider interaction (during services); and to boost adherence and maintenance (after services). The concept includes considerations of social and cultural norms that impact service use (or non-use) and delivery, the physical environment in which services are delivered, and the communication that takes place between a client and provider. Users of this indicator bank should note that, while client behaviors can be influenced by service interactions, they are also influenced by factors outside of service delivery.

The Circle of Care

Figure 3: The Circle of Care model

The Circle of Care model (see Figure 3) is a framework for understanding how SBC interventions can be used along the service delivery continuum—before, during and after services. Three key principles guide this model:

- Promoting effective coordination among SBC and service delivery partners—encourages a common understanding for program planning, message development, intervention approaches, and monitoring and evaluation

- Segmenting, prioritizing, and profiling key audiences—helps to understand the intended audience and their specific needs, values, and barriers to change

- Addressing providers as a behavior change audience—ensures providers are seen as individuals who have needs and barriers to adopting desired behaviors related to their performance.

All of the SBC for service delivery indicators in this bank are classified by stage of the Circle of Care: before, during, after, or cross-cutting. Read more about the Circle of Care.

Indicator Bank

| Construct | Indicator | Indicator Type | Indicator Level | Potential disaggregation | Calculation (if applicable) | Circle of Care stage | Service Delivery Indicators | Additional Key Search Term(s) | Potential data source(s) | Source web link |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support of FP collaboration and coordination | Number of meetings that foster technical FP coordination and collaboration between country partners | Output | Policy and environment | None | No | process | Program records | |||

| Development of FP communication materials | Number of communication materials developed for FP in the last 12 months (or a specific reference period) | Output | Health service delivery | By type of materials (e.g., print, billboard, mobile application) | No | process | Program records | |||

| Dissemination of FP communication materials | Number of communication FP materials disseminated in the last 12 months (or a specific reference period) | Output | Community, Health service delivery | By geographic area and type of material (e.g., print, billboard, mobile application) | No | process | Program records | |||

| Dissemination of FP mass media messages | Number of times FP messages were aired on television or radio in the last 12 months (or a specific reference period) | Output | Community | By radio or television | No | mass media, broadcasting, process | Program records | |||

| Dissemination of FP mass media messages | Percentage of FP broadcasts aired at the requested time | Output | Community | By radio or television | Numerator: Number of FP broadcasts that aired at the requested time Denominator: Total number of FP broadcasts requested to be aired at a specific time |

Yes | mass media, television, radio, process | Program records, Broadcast logs | ||

| Implementation of SBC FP interventions | Number of SBC interventions implemented to support or improve FP services | Output | Community, Health service delivery | None | Before | No | process | Program records | ||

| Community-level FP activities | Number of community-level activities for FP conducted in project sites | Output | Community | By geographic area, type of activity (e.g. community dialogues, support groups, commodity distribution, household visits, mobile clinics) | No | process | Program records | |||

| FP provider training | Number of service providers trained in interpersonal communication for FP counseling | Reach-coverage | Health service delivery | By type of provider (community- or facility-based), sex | Before | No | provider counseling, provider-client communication | Program records | ||

| Reach of FP advocacy | Number of decision makers reached with FP advocacy activities | Reach-coverage | Policy and environment | By type of decision maker (e.g., politician, health facility administrator, religious leader) | Yes | Program records | ||||

| Dissemination of FP communication materials to service providers | Number of service providers who received FP communication materials | Reach-coverage | Health service delivery | By geographic area, type of provider (community- vs. facility-based), type of materials (e.g., print, billboard, mobile application) | Before | No | Program records | |||

| Reach of FP messages, campaigns, or communication initiatives | Percentage of intended audience who recall hearing or seeing a specific FP message/campaign/communication initiative* | Reach-coverage | Individual, Community | By geographic area, sex, age category, marital status, parity, source of information (e.g., print, radio, TV, SMS) | Numerator: Number of individuals from the intended audience who recall FP message/campaign/communication initiative Denominator: Total number of individuals within the intended audience |

No | exposure | Community-based surveys | ||

| Coverage of FP mass media messages | Estimated number of intended audience in program areas reached by FP mass media | Reach-coverage | Community | By type of mass media (e.g., radio, TV), geographic area | No | exposure | Media ratings, Community-based surveys | |||

| Participation in community-level FP activities | Number of community members participating in community-level activities for FP in the last six months | Reach-coverage | Community | By geographic area, sex, age category, activity type (e.g., community dialogues, support groups, commodity distribution, household visits, mobile clinics) | Yes | Program records | ||||

| Reach of information from provider | Percentage of intended audience who reported that they received FP information from a facility- or community-based health provider in the last 12 months (or a specified reference period)* | Reach-coverage | Individual, Community | By geographic area, sex, age category, current marital status, parity, community, or facility source | Numerator: Number of individuals from the intended audience that received FP information from a facility- or community-based health provider in the last 12 months Denominator: Total number of individuals within the intended audience |

Cross-cutting | No | provider counseling, provider-client communication, quality of health care | Household surveys, Client exit interviews, SMS/telephone surveys | |

| National capacity strengthening about FP | National FP communication strategy approved by the ministry | Intermediate outcome | Policy and environment | None | No | |||||

| Policy advocacy about FP | Number of government leaders who speak out in favor of FP | Intermediate outcome | Policy and environment | By type of government leader (local, regional, national) | Yes | Media and community monitoring records | ||||

| Provider-client communication about FP | Percentage of women of reproductive age that were informed of other FP methods besides their preferred method, among those that visited an FP provider in the past 12 months (or a specified reference period) | Intermediate outcome | Individual | By geographic area, age category, current marital status, parity | Numerator: Among women of reproductive age (15-49 years) that visited an FP provider in the past 12 months, the number that report that their FP provider informed them of other FP methods besides their preferred method Denominator: Total number of women of reproductive age (15-49 years) that visited an FP provider in the past 12 months |

During | Yes | provider counseling, provider-client communication, quality of care | Household surveys, Client exit interviews, SMS/telephone surveys | |

| Provider-client communication about FP | Percentage of women of reproductive age who were informed of potential side effects of any type of FP method during their visit, among those that visited an FP provider in the past 12 months (or a specified reference period) | Intermediate outcome | Individual | By geographic area, sex, age category, current marital status, parity | Numerator: Among women of reproductive age (15-49 years) that visited an FP provider in the past 12 months, the number who report having discussed an FP method and being informed about potential side effects of any FP method (not FP in general) Denominator: Total number of women of reproductive age (15-49 years) that visited an FP provider in the past 12 months and discussed an FP method |

During | Yes | provider counseling, provider-client communication, quality of care | Household surveys, Client exit interviews, SMS/telephone surveys | |

| Attitudes toward FP providers | Percentage of intended audience members with favorable attitudes towards FP providers* | Intermediate outcome | Individual, Community | By geographic area, sex, age category, current marital status, parity | Numerator: Number of individuals from the intended audience who agree/strongly agree with statements expressing favorable attitudes towards FP providers Denominator: Total number of individuals within the intended audience |

Cross-cutting | No | patient satisfaction | Household surveys, Client exit interviews, SMS/telephone surveys | |

| Injunctive norms about FP | Percentage of intended audience who believe that most people in their community approve of people like them using FP* | Intermediate outcome | Individual, Community | By geographic area, sex, age category, current marital status, parity | Numerator: Number of individuals from the intended audience who agree/strongly agree with the statement "Most people in my community approve of people like me using FP" Denominator: Total number of individuals within the intended audience |

No | injunctive norm, social norm, societal norm, social support | Household surveys, Client exit interviews, SMS/telephone surveys | ||

| Intention to use FP | Percentage of non-users of intended audience who intend to adopt FP in the next three months | Intermediate outcome | Individual | By geographic area, sex, age category, current marital status, parity, type of FP method | Numerator: Among individuals from the intended audience who are currently not using an FP method, the number that report they intend to start using an FP method in the next three months Denominator: Total number of individuals within the intended audience who are not currently using an FP method |

No | intention | Household surveys, Client exit interviews, SMS/telephone surveys | ||

| Intention to continue to use FP | Percentage of modern FP users who intend to continue using a modern FP method | Intermediate outcome | Individual | By geographic area, sex, age category, current marital status, parity, type of FP method | Numerator: Among individuals of reproductive age (15-49 years for women; 15-59 years for men) that are currently using a modern FP method, the number that report they intend to continue using a modern FP method Denominator: Total number of individuals of reproductive age (15- 49 years for women; 15-59 years for men) currently using a modern FP method |

No | intention, maintenance, contraceptive, continuation | Household surveys, Client exit interviews, SMS/telephone surveys | ||

| Attitudes toward FP | Percentage of intended audience with favorable attitudes towards FP* | Intermediate outcome | Individual, Community | By geographic area, sex, age category, current marital status, parity | Numerator: Number of individuals from the intended audience who agree/strongly agree with statements expressing favorable attitudes towards FP Denominator: Total number of individuals within the intended audience |

No | social norm, societal norm | Household surveys, Client exit interviews, SMS/telephone surveys | ||

| Attitudes toward modern FP methods | Percentage of intended audience with favorable attitudes towards modern FP methods* | Intermediate outcome | Individual, Community | By geographic area, sex, age category, current marital status, parity | Numerator: Number of individuals from the intended audience who agree/strongly agree with statements expressing favorable attitudes towards modern FP methods Denominator: Total number of individuals within the intended audience |

No | social norm, societal norm | Household surveys, Client exit interviews, SMS/telephone surveys | ||

| Knowledge of FP methods | Percentage of intended audience who know of at least three modern FP methods* | Intermediate outcome | Individual, Community | By geographic area, sex, age category, current marital status, parity | Numerator: Number of individuals from the intended audience who can correctly name at least three modern FP methods Denominator: Total number of individuals within the intended audience |

Yes | knowledge, contraceptive | Household surveys, client exit interviews, SMS/telephone surveys | ||

| Knowledge of FP sources | Percentage of intended audience who know where to obtain FP in their community* | Intermediate outcome | Individual, Community | By geographic area, sex, age category, current marital status, parity | Numerator: Number of individuals of intended audience who can correctly name at least one source of obtaining FP services/supplies in their community Denominator: Total number of individuals within the intended audience |

Before | No | knowledge, access, availability, accessibility | Household surveys, Client exit interviews, SMS/telephone surveys | |

| Self-efficacy for using FP | Percentage of individuals of reproductive age who are confident in their ability to use FP | Intermediate outcome | Individual | By geographic area, sex, age category, current marital status, parity, use status (never users, non-users) | Numerator: Number of individuals from the intended audience that agree/strongly agree that they are confident in their ability to use FP (or a specific type of FP method) Denominator: Total number of individuals within the intended audience |

No | self-efficacy | Household surveys, Client exit interviews, SMS/telephone surveys | ||

| Joint decision-making | Percentage of intended audience who decided jointly with their spouse/partner which FP method to use* | Intermediate outcome | Individual, Community | By geographic area, sex, age category, parity, type of method | Numerator: Number of individuals from the intended audience, currently in union, who report that they chose their FP method jointly with their spouse/partner Denominator: Total number of individuals within the intended audience, currently in union |

No | interpersonal communication, partner communication, social interaction, interpersonal relations, husband-wife communication, spousal communication, contraceptive | Household surveys, Client exit interviews, SMS/telephone surveys | ||

| Attitudes toward FP | Percentage of intended audience who approve of FP use | Intermediate outcome | Individual | By geographic area, sex, age category, current marital status, parity, type of FP method | Numerator: Number of individuals from the intended audience who agree/strongly agree with the statement "I think it is okay for people to use FP" Denominator: Total number of individuals within the intended audience |

No | social support, attitude, societal norm | Household surveys, Client exit interviews, SMS/telephone surveys | ||

| Normative beliefs about FP | Percentage of intended audience who believe that their religious leaders would approve of people like them using FP* | Intermediate outcome | Individual, Community | By geographic area, sex, age category, current marital status, parity | Numerator: Number of individuals from the intended audience who agree/strongly agree with the statement "My religious leader(s) would approve of people like me using FP" Denominator: Total number of individuals within the intended audience |

No | social norm, opinion leader, societal norm, social support | Household surveys, Client exit interviews, SMS/telephone surveys | ||

| Normative beliefs about FP | Percentage of intended audience who believe that their spouse/partner would approve of them using FP* | Intermediate outcome | Individual, Community | By geographic area, sex, age category, parity | Numerator: Number of individuals from the intended audience, currently in union, who agree/strongly agree with the statement "My spouse/partner would approve of me using FP" Denominator: Total number of individuals within the intended audience, currently in union |

No | social support, societal norm, social norm, partner communication, husband-wife communication, spousal communication, interpersonal relationships | Household surveys, Client exit interviews, SMS/telephone surveys | ||

| Normative beliefs about modern FP methods | Percentage of intended audience who believe that their spouse/partner approve of them using a modern FP method | Intermediate outcome | Individual | By geographic area, sex, age category, parity | Numerator: Number of individuals from the intended audience currently in union who agree/strongly agree with the statement "My spouse/partner would approve of me using __________" (battery of separate questions for each type of FP method) Denominator: Total number of individuals within the intended audience, currently in union |

No | social support, societal norm, social norm, partner communication, husband-wife communication, spousal communication, interpersonal relationships | Household surveys, Client exit interviews, SMS/telephone surveys | ||

| Normative beliefs about FP | Percentage of intended audience who believe that their spouse/partner would approve of them using FP to space pregnancies* | Intermediate outcome | Individual, Community | By geographic area, sex, age category, current marital status, parity | Numerator: Number of individuals from the intended audience currently in union who agree/strongly agree with the statement " My spouse/partner would approve of me using FP to space our next pregnancy" Denominator: Total number of individuals within the intended audience currently in union |

No | spacing, social support, societal norm, social norm, partner communication, husband-wife communication, spousal communication, interpersonal relations | Household surveys, Client exit interviews, SMS/telephone surveys | ||

| Normative beliefs about FP | Percentage of intended audience who believe that their spouse/partner would approve of them using FP to limit pregnancy* | Intermediate outcome | Individual, Community | By geographic area, sex, age category, current marital status, parity | Numerator: Number of individuals from the intended audience, currently in union, who agree/strongly agree with the statement, "My spouse/partner would approve of me using FP to not have any more pregnancies" Denominator: Total number of individuals within the intended audience, currently in union |

No | social support, societal norm, social norm, partner communication, husband-wife communication, spousal communication, interpersonal relationships | Household surveys, Client exit interviews, SMS/telephone surveys | ||

| Partner communication about FP | Percentage of intended audience who discussed FP with their spouse/partner in the last 12 months and think their spouse/partner values their opinion on whether to use FP* | Intermediate outcome | Individual, Community | By geographic area, sex, age category, current marital status, level of education, employment status | Numerator: Number of individuals from the intended audience, currently in union who have discussed FP use with their spouse/partner in the last 12 months, and that agree/strongly agree with the statement, "My spouse/partner values my opinion on whether to use FP"|

| Yes |

reproductive empowerment, partner communication, husband-wife communication, social interaction, spousal communication, interpersonal relations |

Household surveys, Client exit interviews, SMS/telephone surveys |

| |

| Satisfaction with FP provider | Percentage of women of reproductive age who would refer others to their FP provider, among those who have visited a FP provider in the last 12 months | Intermediate outcome | Individual | By geographic area, age category, current marital status, parity, FP method | Numerator: Number of women of reproductive age (15-49 years) who would refer a relative or a friend to their FP provider, among those who visited a FP provider in the last 12 months Denominator: Total number of women of reproductive age (15-49 years) who visited a FP provider in the last 12 months |

Cross-cutting | No | patient satisfaction, patient preference | Client exit interviews | |

| Provider use of FP communication materials | Percentage of FP service providers reporting the use of communication FP materials in the past three months (or a specified reference period) | Behavioral outcome | Health service delivery | By geographic area, type of provider (community- or facility-based), sex | Numerator: Number of FP service providers that report having used communication materials on FP in the past three months (or a specified reference period) Denominator: Total number of FP service providers |

During | No | quality of care | Provider survey | |

| Partner communication about FP | Percentage of individuals of the intended audience who talked about FP with their spouse/partner in the last 12 months (or a specified reference period)* | Behavioral outcome | Individual, Community | By geographic area, sex, age category, parity | Numerator: Number of individuals from the intended audience in union who reported having talked about FP with their spouse/partner in the last 12 months Denominator: Total number of individuals within the intended audience currently in union. |

No | interpersonal communication, interpersonal relations, social interaction, partner communication, husband-wife communication, spousal communication | Household surveys, Client exit interviews, SMS/telephone surveys | ||

| Interpersonal communication about FP | Percentage of individuals of intended audience who talked about FP with others (friends, relatives, community) in the last 12 months (or a specified reference period)* | Behavioral outcome | Individual, Community | By geographic area, sex, age category, current marital status, parity, which "other" they talked to | Numerator: Number of individuals from the intended audience who reported having talked about FP with others (friends, relatives, community) in the last 12 months Denominator: Total number of individuals within the intended audience |

No | interpersonal communication, client satisfaction, interpersonal relations, social interaction, partner communication, husband-wife communication, spousal communication | Household surveys, Client exit interviews, SMS/telephone surveys | ||

| Interpersonal communication about FP | Percentage of intended audience that has encouraged others (friends, relatives, community) to use FP in the last 12 months (or a specified reference period)* | Behavioral outcome | Individual, Community | By geographic area, sex, age category, category of persons they encouraged | Numerator: Number of individuals from the intended audience who reported having encouraged others (friends, relatives, community) to use FP in the last 12 months Denominator: Total number of individuals within the intended audience |

Yes | champion, personal advocacy, social interaction, interpersonal relations | Household surveys, Client exit interviews, SMS/telephone surveys | ||

| Interpersonal communication about FP | Percentage of women of reproductive age who have talked with a FP provider in the last 12 months | Behavioral outcome | Individual | By geographic area, sex, age category, parity, type of FP user (e.g. non-user versus user), type of FP provider | Numerator: Number of women of reproductive age (15-49 years) who reported that they talked with a FP provider in the last 12 months Denominator: Total number of women of reproductive age (15-49 years) |

During | Yes | interpersonal communication, interpersonal relations, social interaction, provider-patient communication, client-provider communication | Household surveys, SMS/telephone surveys | |

| Use of FP services | Percentage of women of reproductive age who have accessed FP services in the last 12 months | Behavioral outcome | Individual | By geographic area, sex, age category, parity, sector (public/private), type of facility/provider (e.g. community health center, community health worker, pharmacy/drug shop) | Numerator: Number of women of reproductive age (15-49 years) who reported that they have accessed FP services in the last 12 months Denominator: Total number of women of reproductive age (15-49 years) |

During | No | health service utilization | Household surveys, SMS/telephone surveys | |

| Use of a modern FP method | Percentage of women of reproductive age in union who are using, or whose male partner is using, a modern FP method | Behavioral outcome | Individual | By geographic area, age category, current marital status, parity, FP method | Numerator: Number of women of reproductive age (15-49 years) who reported that they are currently using, or whose male partners are using, a modern FP method Denominator: Total number of women of reproductive age (15-49 years) in union |

Yes | modern contraceptive prevalence rate, contraceptive | Household surveys, Client exit interviews, SMS/telephone surveys | ||

| Satisfaction with FP services | Percentage of women of reproductive age currently using a modern FP method, reporting they obtained their contraceptive method of choice | Intermediate outcome | Individual | By geographic area, age category, current marital status, parity, FP method | Numerator: Number of women who reported that they obtained their FP method of choice, among women of reproductive age (15-49 years) using a modern FP method Denominator: Number of women of reproductive age (15-49 years) currently using a modern FP method |

Cross-cutting | No | reproductive empowerment, contraceptive | Household surveys, Client exit interviews | |

| Use of long acting FP method | Percentage of women of reproductive age using (or whose partner is using) a long-acting modern FP method | Behavioral outcome | Individual | By type (reversible/permanent) | Numerator: Number of women of reproductive age (15-49 years) who reported that they (or their partner) are using a long-acting FP method (IUD, implant, male/female sterilization) Denominator: Total number of women of reproductive age (15-49 years) |

Yes | sterilization, permanent, contraceptive, LARC, implant, IUD | Household surveys, Client exit interviews, SMS/telephone surveys | ||

| Counseling | Percent of maternal and child health services clients who received counseling about the lactational amenorrhea method (LAM) | Provider behavioral outcome | Health service delivery | By the type of maternal and child health services (e.g., antenatal, labor and delivery, or postpartum), the type of facility or program (e.g., public, private, non-governmental, community-based), and where data are available by other relevant factors, such as women’s age <20 years vs. ≥20 years, parity, and urban/rural location | Numerator: Number of women attending maternal and child health services who received LAM counseling Denominator: Total number of women who attended maternal and child health services during a specified time period Maternal and child health services may include antenatal care, labor and delivery, postpartum visit, and/or infant and child health/immunization visits. For women delivering at a facility, counseling should be conducted prior to discharge. It should consist of an evaluation for LAM use, instruction on the method including information that LAM is 98% effective in preventing pregnancy when used correctly, and the need for immediate transition to another modern method when any of the LAM criteria are no longer being met. The three criteria for correct LAM use are: 1. The mother’s period has not returned. 2. The infant is exclusively breastfed and the time between feedings should not be longer than four hours during the day or six hours at night. 3. The infant is less than six months old. | During | Yes | Facility records, Hospital information system, Client exit interviews, Special studies | MEASURE Evaluation | |

| Counseling | Percent of service delivery points that offer FP to postabortion care clients | Output | Health service delivery | By geographic area, urban/rural location | Numerator: Number of service delivery points offering FP counseling and methods to postabortion care patients Denominator: Total number of service delivery points offering postabortion care | During | Yes | Facility records, Provider survey, Client exit interviews, Service observation | MEASURE Evaluation | |

| Counseling | Percent of postabortion clients who were counseled on FP | Provider behavioral outcome | Health service delivery | By age group, <20 years vs. ≥20 years | Numerator: Number of women receiving contraceptive counseling after postabortion services Denominator: Total number of women receiving postabortion care services Postabortion services include triage, stabilization, referral for emergency treatment, or emergency treatment services for complications related to miscarriage or unsafe abortion during the past year regardless of location of services. In hospitals in developing countries, treatment of abortion complications may be performed in many different locations within the facility, such as the gynecological ward, emergency room, or operating room. Data collection should, therefore, include encounters from all locations. | During | Yes | Facility records, Special studies | MEASURE Evaluation | |

| Counseling | Number/percent of women who delivered in a facility and received counseling on FP prior to discharge | Provider behavioral outcome | Health service delivery | By geographic area, age group <20 years vs. ≥20 years | Numerator: Number of women who delivered in a facility and received counseling on FP prior to discharge Denominator: Number of women who delivered in a facility Counseling should consist of information on benefits of healthy timing and spacing of pregnancy, return to fertility after birth, return to sexual activity, safe modern FP options for postpartum women including those breastfeeding (based on WHO’s medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use), LAM, and transition from LAM to a modern method. | During | Yes | Facility records | FP2020 | |

| Discontinuation | Contraceptive discontinuation rate | Client behavioral outcome | Individual | By contraceptive method, reason for discontinuation (e.g., method failure, desire for pregnancy, other fertility related reasons, side effects/health concerns, wanted more effective method, other method related reasons, switched to another method, or other reasons), type of discontinuation (whether the woman discontinued while in need of contraception, or discontinued because she is not in need of contraception) | Numerator: Number of episodes where a specific FP method is discontinued within 12 months after beginning its use Denominator: Number of episodes of FP use among women of reproductive age who began an episode of contraceptive use 3–62 months before being interviewed Users who switch to another method are considered to have discontinued the previous method at the time of switching. | After | Yes | DHS surveys | FP2020 | |

| Discontinuation | Method switching | Client behavioral outcome | Individual | By contraceptive method | Numerator: Number of episodes of FP use where the specific FP method is discontinued within 12 months after beginning its use, and use of a different method begins after no more than one month of non-FP use Denominator: Number of episodes of FP use among women of reproductive age who began an episode of FP use 3–62 months before being interviewed | After | Yes | DHS surveys | FP2020 | |

| Discontinuation | Reasons for discontinuation of contraceptive methods | Client behavioral outcome | Individual | By contraceptive method | Percent distribution of discontinuations of contraceptive methods in the five years preceding the survey by main reason for discontinuation, according to specific method. | After | Yes | DHS surveys | DHS | |

| Discontinuation | Contraceptive Continuation rate/”all-method“ continuation rate | Client behavioral outcome | Individual | The indicator (CRx) is calculated as: CRx = x(1-qx)/π Where: x = 1 qx = Tx/Nx = conditional probability of discontinuing use during a given interval (e.g., one month, one quarter); Tx = the number of women discontinuing use during the interval; and Nx = number of women using at the beginning of the interval. Note: π signifies that (1 - qx ) is multiplied over all intervals from 1 to x. Data Requirements: Information on contraceptive initiation, duration of use (including method switching), and discontinuation during a given reference period (e.g., the three to five years prior to a survey). Based on this information, one can calculate the percentage who have continuously used for a specific duration (e.g., 12 months, 18 months), as well as the median duration of use. When using cross-sectional population data, evaluators calculate the continuation rate for each unit-interval of use (e.g., first, second, third month of use, and so forth) as the complement of the ratio of acceptors who discontinue use of a program method of contraception at that duration to the number of women still using at the beginning of the month (i.e., 1 minus the discontinuation rate). Evaluators then cumulate these continuation rates to obtain the probability that acceptors of a contraceptive method will still be using any program method after the specified period of time. | After | Yes | Household surveys, Program records | |||

| General SBC | Percent of audience with a favorable (or unfavorable) attitude toward the product, practice, or service | Intermediate outcome | Individual | By product, practice, or service or audience characteristics (e.g., age, sex, geographic location, rural/urban status, or other characteristics of interest to the program) | Numerator: Number of audience members with a favorable (or unfavorable) attitude toward the product, practice, or service Denominator: Total number of audience members “Favorable attitude” is defined as a person’s positive assessment of a behavior or related construct (such as a specific product or source of service). “Unfavorable attitude” is defined as a person’s negative assessment of a behavior or related construct. The assessment is expressed by statements from the audience that relate the behavior to a positive or negative value held by the audience. Evaluators measure attitude by asking audience members how strongly they agree or disagree with these statements, usually in terms a five-point (Likert-type) scale. For more examples, see: https://www.measureevaluation.org/prh/rh_indicators/service-delivery/sbcc/percent-of-audience-with-a-with-a-favorable | Before | Yes | Household surveys, Client exit interviews, SMS/telephone surveys, Focus groups, Ethnographic observation | MEASURE Evaluation | |

| Provider knowledge | Percent of providers at maternal and child health service delivery points who know the range of contraceptive options that do not interfere with breastfeeding | Intermediate outcome | Health service delivery | By the type of provider, type of facility (e.g., public, private, non-governmental, community based), or other relevant factors such as districts and urban/rural location | Numerator: Number of providers at maternal and child health service delivery points who know contraceptive options during breastfeeding Denominator: Total number of providers at service delivery points in a designated area during a specified time period Service delivery points include all public, private, non-governmental, and community-based health facilities and outlets in which maternal and child health services are offered, including antenatal care, labor and delivery, postpartum, and/or infant and child care. | Before | Yes | Provider survey, Special studies | MEASURE Evaluation | |

| Quality | 10-item process quality measure index | Provider behavioral outcome | Health service delivery | See https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/sifp.12093 for calculation details. Survey questions include the following: When you first adopted your current method, did the provider: Ask about whether you would like to have a/another child? Ask about when you would like to have a/another child? Ask about your previous FP experience? Ask about your FP method preference? Talk about possible side effects or problems with the method you selected? Tell you what to do if you experience any side effects or problems with the method you selected? Talk about warning signs associated with the method you selected? Talk about the possibility of switching to another method if the method you selected was not suitable? When meeting with the provider during your visit, do you think other clients could see you? When meeting with the provider during your visit, do you think other clients could hear what you said? | During | Yes | Client exit interviews, Household surveys | Wiley Library | ||

| Referral | Percent of clients referred to other FP services | Provider behavioral outcome | Health service delivery | By type of service delivery point, type of referral provided (e.g., method, referral destination), client characteristics (e.g., age, sex, geographic location, and rural/urban status), original intention of visit (e.g., FP services or other services) | Numerator: Number of FP clients who received a referral for an FP service during the reference period Denominator: Total number of FP clients served at the service delivery points during the reference period A referral occurs if the client is advised where he or she can go to find their preferred or recommended FP method not provided at the original service delivery point, and the referral is documented at the referral source as proof that a referral was made. FP clients are those who received screening for FP need and/or FP counseling at the service delivery point, regardless of the original intention of the visit. | During, After | Yes | Facility records | MEASURE Evaluation | |

| Uptake | Percent of married women under age 18 exposed to Healthy Timing and Spacing of Pregnancy (HTSP) counseling/education who subsequently adopted an FP method to delay first pregnancy | Client behavioral outcome | Individual | By age of respondent <20 years vs. ≥20 years, site, underserved population, vulnerable group, FP method adopted, or type of counseling/education | Numerator: Number of married women under age 18 exposed to HTSP counseling/education surveyed/interviewed who subsequently adopted an FP method to delay first pregnancy Denominator: Total number of married women under age 18 exposed to HTSP counseling/education surveyed/interviewed To calculate this indicator, the women surveyed/interviewed must answer affirmatively to both questions: 1. In the past (specified period of time, e.g., 12 months), have you heard or read about messages related to HTSP through the radio, TV, brochures, other media, or from a health provider, community leader, or other individual? 2. Since hearing about HTSP, have you adopted an FP method to delay your first pregnancy? | After | Yes | Program records, Special studies, Client exit interviews | MEASURE Evaluation | |

| Uptake | Percent of postabortion clients who leave the facility with a modern contraceptive | Client behavioral outcome | Individual | By type of method, or age group <20 years vs. ≥20 years | Numerator: Number of women who received postabortion care services and left the facility with a contraceptive method Denominator: Total number of women receiving postabortion care services Postabortion care includes triage, stabilization, referral for emergency treatment, or emergency treatment services for complications related to miscarriage or unsafe abortion during the past year regardless of location. Note: In hospitals in developing countries, treatment of abortion complications may be performed in many different locations within the facility, such as the gynecological ward, emergency room, or operating room; data collection should, therefore, include encounters from all locations. | During | Yes | Special studies, Facility records | MEASURE Evaluation | |

| Uptake | Number/percent of women who deliver in a facility and initiate or leave with a modern contraceptive method prior to discharge | Client behavioral outcome | Individual | By geographic area, method, or age group <20 years vs. ≥20 years | Numerator: Number of women who receive a method inserted by a provider (IUD, implant) or tubal ligation, women who start using LAM, and women who leave with a method (pills, condoms) Denominator: Number of women who delivered in a facility | During | Yes | Facility records | FP2020 | |

| Provider knowledge | Percent of health and non-health workers trained in HTSP who can state the three HTSP recommendations, by type of trainee | Intermediate outcome | Health service delivery | By type of trainee (e.g., doctors, nurses, community health workers, community leaders, or traditional birth attendants) or socioeconomic status of areas served by trainees | Numerator: Number of health and non-health workers trained in HTSP who can correctly state the three HTSP recommendations Denominator: Total number of health and non-health workers trained in HTSP The three HTSP recommendations that must be stated correctly are: 1. After a live birth, the recommended interval before attempting the next pregnancy should be at least 24 months (this is equivalent to a 33-month birth-to-birth interval). 2. After a miscarriage or induced abortion, the recommended minimum interval to next pregnancy should be at least six months. 3. First pregnancy should be delayed until at least 18 years of age. | Before | Yes | Training evaluations | MEASURE Evaluation | |

| Counseling | Percent of women who received FP information for pregnancy spacing during a postpartum/postabortion visit, by type of visit | Provider behavioral outcome | Health service delivery | By type of visit (postabortion or postpartum), what form the information was received in (counseling and/or printed materials), age of woman <20 years vs. ≥20 years, parity, site, underserved population, or vulnerable group | Numerator: Number of women presenting for postpartum or postabortion care who received FP information that included HTSP messages Denominator: Total number of women attending for postpartum or postabortion care The FP information received, which includes HTSP messages, may be in the form of counseling and/or printed materials. Only postpartum and postabortion care visits are included. HTSP information includes risks, benefits, and messages. | During | Yes | Program records, Health information systems, Special studies, Client exit interviews | MEASURE Evaluation | |

| Uptake | Percent of women with a child under age two exposed to HTSP counseling/education who subsequently adopted an FP method in order to space their next pregnancy | Client behavioral outcome | Individual | By age of respondent <20 years vs. ≥20 years, site, parity, underserved population, vulnerable group, FP method adopted, or type of counseling/education received | Numerator: Number of women (with a child <2 years old) exposed to HTSP counseling/education surveyed/interviewed who subsequently adopted an FP method to space their next pregnancy Denominator: Total number of women (with a child <2 years old) exposed to HTSP counseling/education who are surveyed/interviewed To calculate this indicator, the women surveyed/interviewed must answer affirmatively to both questions: 1. In the past (specified period of time, e.g., 12 months), have you heard or read about messages related to HTSP through the radio, TV, brochures, other media, or from a health provider, community leader, or other individual? 2. Since hearing about HTSP, have you adopted an FP method to space your next pregnancy? | After | Yes | Program records, Health information systems, Special studies, Client exit interviews | MEASURE Evaluation | |

| Training | Number of health providers trained in long-acting and permanent methods | Output | Health service delivery | By sex, type of provider, method(s) trained in, type of training (pre-service or in-service), or socio-economic status of areas served by trainees | In a defined time period (e.g., one year), number of doctors, nurses, and auxiliary staff who receive pre-service or in-service training in the provision of long-acting and permanent methods of FP, all together and broken down by kind of service provider and kind of method. “Training” can refer to any type of long-acting and permanent methods training event, regardless of its duration or location. It involves a trainee getting a thorough understanding of the essential knowledge required to perform the job and progressing from either lacking skills or having minimal skills to being proficient. | Before | Yes | Training logs | MEASURE Evaluation | |

| Training | Percent of health workers trained to provide adolescent and youth-friendly services | Output | Health service delivery | By socio-economic status of areas served by trainees | Numerator: Number of program staff who have received specific training to provide education/ counseling or adolescent healthcare Denominator: Total number of program staff working with adolescents | Before | Yes | Training logs | MEASURE Evaluation | |

| Provider knowledge | Percent of trainees competent to provide specific services upon completion of training | Intermediate outcome | Health service delivery | Numerator: Number of trainees delivering services according to set standards Denominator: Total number of trainees tested “Competence” refers to the trainee's ability to deliver a service according to a set standard, which may differ according to the training context. Examples may include clinical guidelines or programmatic guidelines set at the national or international level. | Before | Yes | Training evaluations, Service observation | MEASURE Evaluation | ||

| Use/uptake | Method mix | Client behavioral outcome | Individual | Numerator: Number of users of a specific method Denominator: Total number of contraceptive users This indicator is calculated for each method. | Cross-cutting | Yes | Facility records, DHS surveys | MEASURE Evaluation | ||

| Counseling | Percent of long-acting or permanent method counseling sessions that were deemed high quality and comprehensive | Provider behavioral outcome | Health service delivery | By sex, age and parity of individuals being counseled, sex and age of the provider, or socio-economic status of areas served by outlets | Numerator: Number of observed long-acting or permanent method counseling sessions that were deemed high quality and comprehensive Denominator: Total number of observed long-acting or permanent method counseling sessions Data is compiled using a checklist of quality components in a long-acting or permanent method counseling session collected by trained observers who attend counseling sessions. See the Sample Medical Monitoring Checklists by the ACQUIRE Project/EngenderHealth at: http://www.acquireproject.org/fileadmin/user_upload/ACQUIRE/Facilitative-Supervision/Trainers-Manual/FS_TM_Appendixes_A-F/fs_tm_appendix_a.pdf | During | Yes | Service observation, Client exit interviews | MEASURE Evaluation | |

| General SBC | Percent of nonusers who intend to adopt a certain practice in the future | Intermediate outcome | Individual | By audience characteristics (age, sex, geographic location, rural/urban status, or other characteristics of interest to the program) | Numerator: Number of audience members who do not currently practice the behavior who intend to adopt the behavior in the specified reference period Denominator: Total number surveyed in intended audience This indicator measures the intention of non-users to adopt a behavior. “Non-users” are those individuals in the intended audience who do not yet practice the behavior in question. “Intend” is operationally defined as the percent of non-users who answer affirmatively to the question, “Do you intend to ___ (practice a specific health behavior) in the future.” Programs should define the period (e.g., in the next 3, 6, or 12 months). “Practice” refers to the desired result the program is trying to achieve among members of the population in question. | Before | Yes | Household surveys, DHS surveys | MEASURE Evaluation | |

| General SBC | Percent of audience who recall hearing or seeing a specific product, practice, or service | Reach-coverage | Individual | By dissemination channel or by audience characteristics (age, sex, geographic location, rural/urban status, or other characteristics of interest to the program) | Numerator: Number of audience members who know about a specific product, practice, or service Denominator: Total number of audience members surveyed “Audience” is defined as the intended population for the program (e.g., pregnant women for antenatal care or youth in a specific age range for an adolescent program). “Recall” refers to the percentage who can spontaneously name (or recognize when mentioned) a particular practice, product, or service. “Recall” refers to the percentage who can spontaneously name (or recognize when mentioned) a particular practice, product, or service. “Practice” refers to the desired behavior the program is promoting among members of a population (e.g., delaying first birth after marriage or exclusively breastfeeding during six-months postpartum). | Before | Yes | Household surveys, DHS surveys, SMS/telephone surveys, Media and community monitoring records | MEASURE Evaluation | |

| General SBC | Percent of audience who practice the recommended behavior | Behavioral outcome | Individual | By audience characteristics (age, sex, geographic location, rural/urban status, or other characteristics of interest to the program) | Numerator: Number of audience members who report practicing the recommended behavior Denominator: Total number surveyed in intended audience “Audience” is defined as the intended population for the program. “Behavior” refers to the desired result the program is trying to achieve among members of the intended population. Depending on the need for a yes/no response, or if the responses lend themselves to more flexibility, evaluators may want to use a five-point Likert scale to decide whether to combine “always practice” with “sometimes practice” to arrive at the total percentage practicing the desired behavior. | After | Yes | Household surveys, Focus groups, In-depth interviews, Ethnographic observation | MEASURE Evaluation | |

| Counseling | Method information index/Informed choice | Provider behavioral outcome | Health service delivery | By method | This index measures the extent to which women were given specific information when they received FP services. The index is composed of three questions: 1. Were you informed about other methods? 2. Were you informed about side effects? 3. Were you told what to do if you experienced side effects?). The reported value is the percent of women who responded “yes” to all three questions. | During | Yes | DHS surveys, PMA2020 surveys | FP2020 | |

| Provider attitudes | Percentage of FP/RH providers with negative attitudes toward adolescent pregnancy (aged 10−19 years) | Intermediate outcome | Individual | By sex, age, gender, years of experience, and cadre | Number of providers who report negative attitudes toward adolescent pregnancy DIVIDED BY total number of providers surveyed working in FP/RH service delivery at facility | Cross-cutting | Yes | attitude, social norm, societal norm | Provider survey | Approaching Provider Behavior Change Monitoring and Evaluation with a Social-Ecological Lens: New Frontiers Brief |

| Provider motivation | Percentage of trained FP/RH providers who feel increased motivation to provide comprehensive information on all FP methods to adolescent clients during FP counseling visits | Intermediate outcome | Individual | By sex, age, gender, years of experience, and cadre | Number of providers who report increased motivation DIVIDED BY total number of providers trained at facility | Cross-cutting | Yes | attitude, social norm, societal norm | Provider survey | Van den Broek, N. (2022). Keep it simple—Effective training in obstetrics for low- and middle-income countries. Best practice & research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 80, 25–38. |

| Provider self-efficacy | Percentage of trained FP/RH providers who feel more confident providing comprehensive information on FP methods to clients during FP counseling visits | Intermediate outcome | Individual | By sex, age, gender, years of experience, and cadre | Number of providers who report increased confidence DIVIDED BY total number of providers trained at facility | Cross-cutting | Yes | knowledge, self-efficacy | Training evaluations, Service observation | Van den Broek, N. (2022). Keep it simple—Effective training in obstetrics for low- and middle-income countries. Best practice & research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 80, 25–38. |

| Provider attitudes | Percentage of FP/RH providers who are influenced by religious and faith leaders with negative attitudes toward FP methods | Intermediate outcome | Individual, Community | By sex, age, gender, years of experience, and cadre | Number of providers who report being influenced by religious and faith leaders with negative attitudes toward FP methods DIVIDED BY total number of providers surveyed working in FP/RH service delivery at facility | Cross-cutting | No | interpersonal relations, social norm, opinion leader, societal norm, social support | Provider survey | Approaching Provider Behavior Change Monitoring and Evaluation with a Social-Ecological Lens: New Frontiers Brief |

| Provider attitudes | Percentage of FP/RH providers who are influenced by colleagues with negative attitudes toward adolescent pregnancy | Intermediate outcome | Health service delivery | By sex, age, gender, years of experience, and cadre | Number of providers who report being influenced by colleagues with negative attitudes toward adolescent pregnancy DIVIDED BY total number of providers surveyed working in FP/RH service delivery at facility | Cross-cutting | No | interpersonal relations, social support, attitude, societal norm | Provider survey | Approaching Provider Behavior Change Monitoring and Evaluation with a Social-Ecological Lens: New Frontiers Brief |

| Provider familial support | Percentage of FP/RH providers who receive support with domestic labor from family members | Intermediate outcome | Individual, Community | By sex, age , gender, years of experience, and cadre of the provider, type of family member (such as parent, parent-in-law, grandparent, sibling), whether they live with/near the family member | Number of providers who report receiving support with domestic labor from family members DIVIDED BY total number of providers surveyed working in FP/RH service delivery at facility | Cross-cutting | No | interpersonal relations, social support, attitude, societal norm | Provider survey | Approaching Provider Behavior Change Monitoring and Evaluation with a Social-Ecological Lens: New Frontiers Brief |

| Counseling | Percentage of FP clients treated with respect by FP/RH provider during their most recent FP counseling visit (according to national-level guidelines) | Provider behavioral outcome | Health service delivery | By sex, age, gender, and parity of client, sex age, gender, years of experience, and cadre of the provider | Number of clients who report being treated with respect by provider during most recent FP counseling visit DIVIDED BY total number of clients surveyed after FP counseling visits at facility in last three months | During | Yes | provider counseling, provider-client communication, quality of care, patient satisfaction | Client exit interviews | Approaching Provider Behavior Change Monitoring and Evaluation with a Social-Ecological Lens: New Frontiers Brief |

| Partner support | Percentage of pregnant women who receive support with domestic labor from partners | Intermediate outcome | Individual, Community | By age of pregnant woman, age of partner, current number of dependent children, years of marriage/domestic partnership, whether they live with partners | Number of pregnant women who are partnered and report receiving support with domestic labor DIVIDED BY total number of pregnant women who are partnered in an administrative area (e.g., sub-district) | Cross-cutting | No | social support, partner communication, social interaction, interpersonal relations, husband-wife communication, spousal communication | Household surveys, Focus groups, In-depth interviews, Ethnographic observation, Client exit interviews | Mamo, A., Abera, M., Abebe, L., Bergen, N., Asfaw, S., Bulcha, G., Asefa, Y., Erko, E., Bedru, K. H., Lakew, M., Kurji, J., Kulkarni, M. A., Labonté, R., Birhanu, Z., & Morankar, S. (2022). Maternal social support and health facility delivery in Southwest Ethiopia. Archives of Public Health (Archives belges de sante publique), 80(1), Article 135. |

| Familial support | Percentage of pregnant women who receive support with domestic labor from family members | Intermediate outcome | Individual, Community | By age of pregnant woman, current number of dependent children, type of family member (such as parent, parent-in-law, grandparent, sibling), whether they live with/near family | Number of pregnant women who report receiving support with domestic labor from family members DIVIDED BY total number of pregnant women in an administrative area (e.g., sub-district) | Cross-cutting | No | interpersonal relations, social support, attitude, societal norm | Household surveys, Focus groups, In-depth interviews, Ethnographic observation, Client exit interviews | Mamo, A., Abera, M., Abebe, L., Bergen, N., Asfaw, S., Bulcha, G., Asefa, Y., Erko, E., Bedru, K. H., Lakew, M., Kurji, J., Kulkarni, M. A., Labonté, R., Birhanu, Z., & Morankar, S. (2022). Maternal social support and health facility delivery in Southwest Ethiopia. Archives of Public Health (Archives belges de sante publique), 80(1), Article 135. |

| Partner support | Percentage of male partners who accompany pregnant women partners to reproductive and maternal health visits | Intermediate outcome | Individual, Community | By years of marriage/domestic partnership, whether pregnant women live with partners | Number of male partners observed accompanying pregnant women partners to at least one visit DIVIDED BY total number of clients who are pregnant women and partnered with a man that attended reproductive and maternal health visit at facility in last three months | Cross-cutting | Yes | social support, interpersonal communication, partner communication, social interaction, interpersonal relations, husband-wife communication, spousal communication | Client exit interviews, Service observation | Approaching Provider Behavior Change Monitoring and Evaluation with a Social-Ecological Lens: New Frontiers Brief |

| Provider caseload | Number of clients to whom an FP/RH provider provides services in an average day | Output | Health service delivery | By sex, age, gender, and parity of clients, sex, age, and gender of the provider | Count of number of outpatient visits with clients per provider per day | During | Yes | health service utilization, workload, stress, burnout | Facility records | World Bank. (2021). Service Delivery Indicators Health Survey 2018—Harmonized public use data. |

| Facility infrastructure | Percentage of FP/RH consultation spaces that guarantee physical privacy (according to national-level guidelines) | Intermediate outcome | Health service delivery | By facility type (such as primary, secondary, tertiary), geographic setting (rural, suburban, urban) | Number of FP/RH consultation spaces that guarantee physical privacy DIVIDED BY total number of FP/RH consultation spaces in use at facility | During | Yes | quality of care, provider counseling, provider-client interaction | Client exit interviews, Service observation | World Bank. (2021). Service Delivery Indicators Health Survey 2018—Harmonized public use data. |

| Medical eduation and training | Percentage of providers involved in FP/RH service delivery who perceive deficiencies in medical education and training (Note: Providers includes doctors, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, nurses, and midwives based on country context) | Intermediate outcome | Policy and environment | By sex, age, gender, and cadre of the provider, years of experience, year received medical degree | Number of providers who report perceived deficiencies in medical education and training DIVIDED BY total number of providers surveyed working in FP/RH service delivery at facility | Cross-cutting | No | quality of care, health service utilization | Provider survey, Employee records | Hassa, H., Ayranci, U., Unluoglu, I., Metintas, S., & Unsal, A. (2005). Attitudes to and management of fertility among primary health care physicians in Turkey: An epidemiological study. BMC Public Health, 5, Article 33. |

REFERENCES

Sallis, J.F., Owen, N., Fisher, E.B. (2008). Ecological models of health behavior. In Glanz, K., Rimer, B.K., Viswanath, K. (Eds.) Health Behavior and Health Education; Theory, Research, and Practice (4th edition), (pg. 46). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Storey, D., Figueroa, M.E. (2012). Toward a Global Theory of Health Behavior and Social Change. In R. Obregon & S. Waisbord (Ed.), The Handbook of Global Health Communication, (pp.78). West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

McLeroy, K.R., Bibeau, D., Steckler, A., Glanz K. (1988). An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly, 15 (4):351-377.

MORE INFORMATION